|

Given the focus on race right now, I decided to write about the idea of health disparities. Many people may have heard of Henrietta Lacks, but most have probably not heard of the term health disparities. I have many thoughts and emotions about what happened to George Floyd and the events of the past week, but am still processing everything, so thought I would write about what I know, which is public health.

Healthy People is a plan prepared by the federal government every ten years that “provides science-based, 10-year national objectives for improving the health of all Americans”. Many of the goals and objectives relate to health equity issues. It defines health equity as the “attainment of the highest level of health for all people. Achieving health equity requires valuing everyone equally with focused and ongoing societal efforts to address avoidable inequalities, historical and contemporary injustices, and the elimination of health and health care disparities.” It basically means that we should make sure that everyone has a chance to be as healthy as they can be. Yet, we know from many research studies that health equity does not exist. There are a lot of differences when it comes to how healthy someone can be. These differences are called health disparities. Healthy People 2020 defines health disparity as “a particular type of health difference that is closely linked with social, economic, and/or environmental disadvantage. Health disparities adversely affect groups of people who have systematically experienced greater obstacles to health based on their racial or ethnic group; religion; socioeconomic status; gender; age; mental health; cognitive, sensory, or physical disability; sexual orientation or gender identity; geographic location; or other characteristics historically linked to discrimination or exclusion.” Health disparities relate to a range of different groups, and there are a lot of reasons why one group of people may have worse health than another. A recent example of health disparities relates to COVID-19, since it has impacted more people of color. You can learn about this in a recent NPR article and in an article published in JAMA, a medical journal. Other groups have also been impacted differently by COVID-19 including those with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Another example of health disparities relates to maternal health. Did you know that Black women are much more likely to die during pregnancy and childbirth in the United States? This detailed article from NPR provides personal stories and data about this tragic public health issue. Even before I began my career in public health I was interested in the intersection of health and society. In one class in college I wrote about the women’s health movement of the early 1970’s. And in another class, I wrote a paper about how apartheid in South Africa impacted the health care system. Over the years I have spent a lot of time teaching my students about health disparities and have learned a great deal from my students about their personal experiences with these issues. However, despite teaching about and studying disparities, I still have a lot to learn, especially when it comes to race and health given my lack of personal experience. Due to the events of the past week, I think it is a good time for all of us to learn more about how race and health are interconnected. There are a lot of good articles to read about race and health disparities including this recent one. But I find I learn the most when I read a book about a topic to get a more in-depth perspective, so I put together a list of books about race and health and thought I would share. I have only read one of the books on the list so far; I look forward to reading more. If you decide to purchase any of these books, consider supporting your local independent bookstore, or a black-owned bookstore such as this one near where I used to live in Philadelphia or this one in Chicago that recently donated over $30,000 worth of books to local children. Many black-owned bookstores are located in cities that have been hit hard by both the COVID-19 pandemic and the protests so they can use your support. And if you have other book suggestions, feel free to add them in the comments below! Black Man in a White Coat: A Doctor’s Reflections on Race and Medicine Damon Tweedy, M.D. 2016 Race and medicine Black Pain: It Just Looks Like We’re Not Hurting Terrie M. Williams 2009 Mental health Blood Sugar: Racial Pharmacology and Food Injustice in Black America Anthony Ryan Hatch 2016 Metabolic health Fatal Invention: How Science, Politics, and Big Business Re-Create Race in the Twenty-First Century Dorothy Roberts 2012 Race and science Flatlines: Race, Work, and Healthcare in the New Economy Adia Harvey Wingfield 2019 Black health care professionals The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks Rebecca Skloot 2011 Medical care and research Invisible Visits: Black Middle-Class Women in the American Healthcare System Tina K. Sacks 2019 Healthcare for Black women Just Medicine: A Cure for Racial Inequality in American Health Care Dayna Bowen Matthew 2015 Health disparities Medical Apartheid: The Dark History of Medical Experimentation on Black Americans from Colonial Times to the Present Harriet Washington 2008 Medical research Reproductive Injustice: Racism, Pregnancy, and Premature Birth Dana-Ain Davis 2019 Pregnancy and birth A Terrible Thing to Waste: Environmental Racism and its Assault on the American Mind Harriet Washington 2019 Environmental health

0 Comments

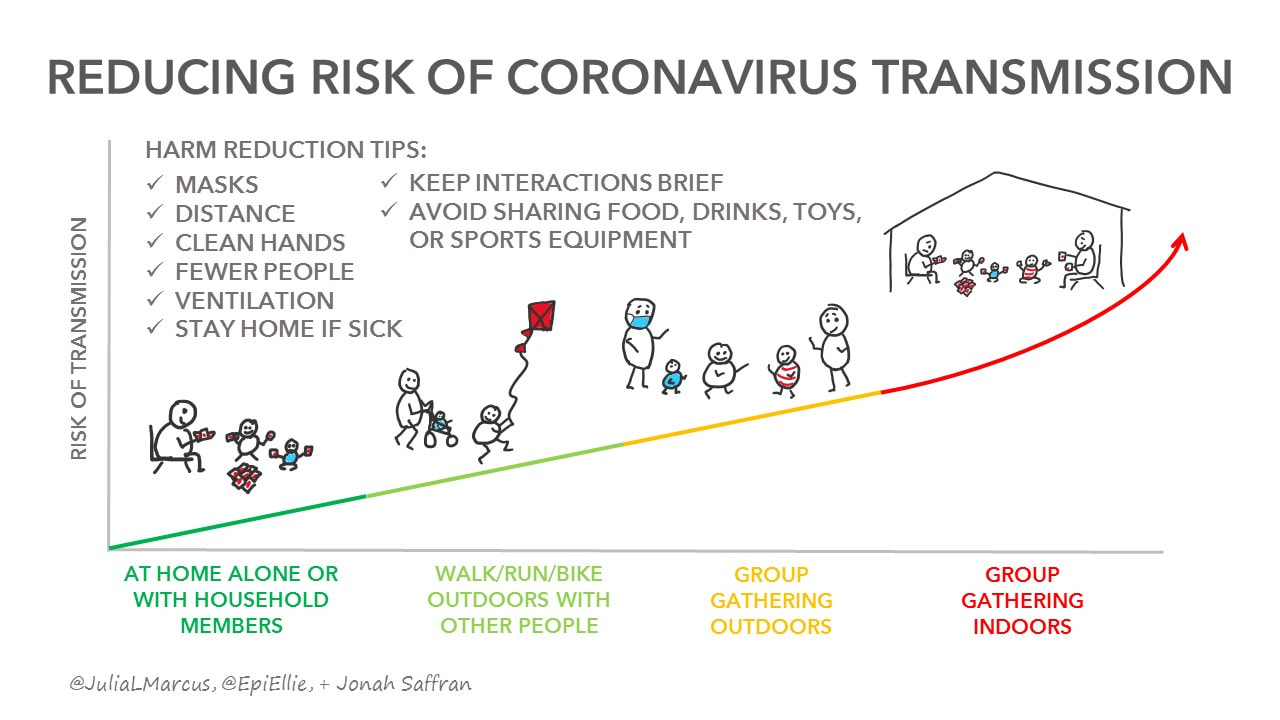

One of my favorite times of the year is when the weather finally starts to get nice in upstate New York. All I want to do is be outside and gather with friends and family. This year is different though. I will be missing many of my traditional summer events such as parades, annual parties, and family reunions due to COVID-19. Recent articles about clusters of cases at a high school swim party in Arkansas, a house party in Minnesota, a birthday party in California, and a church in Arkansas show that group gatherings can be especially problematic since many people are exposed at once. But what is ok to do? I am feeling confused about what is safe and what is risky, especially because we currently have someone who is at risk for complications living in our home. Guidance about actions we can all take to reduce our risk has been changing over time. This is not because the science has been wrong, but rather because the scientists have continued to learn more. It was easier when the guidance was to ‘stay home’. That message was clear. But now, as things start to open back up, there has been confusion about what can open and how, what is ok to do, and how we can still be safe while expanding our activities and social interactions. In public health we talk about something called “harm reduction”. It means that we try to reduce the harm that may occur from health behaviors that can put people at risk. Julia Marcus, a professor at Harvard Medical School, discussed this concept of harm reduction and the need for providing a spectrum of risk in her article about ‘quarantine fatigue’ in The Atlantic. Trying to understand this range of risks can be difficult. There have been a number of useful articles recently written about levels of risk as life opens back up. Some are listed here.

The Dear Pandemic Facebook page has been providing some useful info about various activities. And the infographic below is just one that has been created to help show how risk changes based on activities. These visuals can be especially helpful when trying to convey a range of risks. But even among all of these resources and experts, there is still conflicting information and differences of opinion. Dr. James Stein says in his article “I can’t decide that level of risk for you — only you can make that decision.” This is true. We all have to decide what risks we are comfortable taking. For many the risks a person is willing to (or has to) take may be influenced by several factors including their job, how they get to work, characteristics such as age and pre-existing health conditions, and characteristics of those they are close to. It will also depend on their attitudes about COVID-19, such as what they think about their likelihood of getting it or how bad it will be if they do get it. While we will all make individual choices about risk, it is important to also respect others and to make choices that will avoid putting other people at risk, such as going to a group gathering when you are feeling sick. It can be uncomfortable and frustrating to feel like the information we get is always changing, or that we see different recommendations. Expect that information about risks will continue to change as we learn more. As things open up, it is likely we will see outbreaks due to certain activities or events that will help the experts continue to refine what they know about the risk of different activities and behaviors. Staying informed with credible information sources and asking our health providers questions can help us feel better able to make decisions as we set out to enjoy summer.  Have you heard the term PSA before? It stands for Public Service Announcement. You have probably seen some before. If you are around my age you may remember the one with an egg in a frying pan and someone saying “This is your brain on drugs” from the 1980’s. An advertisement is a brief media message designed to sell a product. It can appear in a variety of formats such as an item in your social media feed, a page in a magazine, or a video message on television. A public service announcement is an “advertisement” but instead of selling a product, it is designed to provide information or change a behavior. PSAs are video or radio files created by health organizations, government agencies, and others. Sometimes the goal is to encourage a healthy behavior, such as getting exercise. Other times the goal is to discourage an unhealthy behavior. For instance, there are many PSAs designed to discourage smoking. PSAs are aired on television and radio stations for free as a way for the stations to provide a service in the interest of the public. This is required by the Federal Communications Commission (FCC). There are many examples of PSAs over the years. The Ad Council is an organization that started during World War II. It was developed through a “collaboration between the advertising, media, and business communities”. People from advertising agencies donate their time to create messages and the media provides free air time to show the messages. They created Smokey the Bear, McGruff the crime dog, and Just Say No. In public health we also talk about mass media campaigns. A public health media campaign gives health messages to the public using different strategies such as PSAs, billboards, bus and subway signs, and social media posts. Media campaigns can be a useful and cost-effective way to get information to a large number of people. People have studied media campaigns and have learned that there are several strategies that can make them more effective. For instance, we need to make sure the messages are provided in places where people will see them which depends on who you are trying to reach. We have also found that it is useful to pre-test messages, meaning that we see if a small group of people respond well to the message before it is provided to a large group of people. A pandemic requires information to be given to people on a very quick timeline. Since PSAs can reach many people quickly and provide information in a clear and easy to understand way, they can be a great resource. PSA's about COVID-19 have been created to provide information about protective actions people can take such as hand washing or to raise awareness about why it is important to stay home. Others provide information about where to get testing or hotline numbers people can call. The Ad Council has been working on several COVID-19 public service announcements including this one about the Centers for Disease Control and another one that uses Elmo to teach children how to wash their hands. New York State created a PSA designed to encourage people to stay home. This example from Saint Lucia is directed at people who interact with children. It is colorful, provides some good tips, and has someone using sign language to make the video more accessible. To see more examples of COVID-19 PSAs from around the world, see my YouTube playlist. On Wednesday of this week, Mayor Garcetti of Los Angeles suggested people wear face masks when going out, and the Governor of Vermont made a similar announcement today. It also came up in the press conference this morning with Governor Cuomo in my state, New York. And, I have seen many friends posting on social media about making and buying cloth face masks. To date, mask guidance from the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) for the general public has stated that people should wear masks if they are sick or caring for someone who is sick (see image below). However, several opinion leaders, officials, and articles have suggested that the CDC may be changing their guidelines on face mask use. Stat news provides a good update about these potential changes. They explain the main idea is that it might help prevent the spread of COVID-19 from people who are not having symptoms (if you have symptoms you should be staying home). In another article published this week by Ed Yong in the Atlantic, you can read a thorough overview of the mask discussions. He cites a few studies that show that homemade masks can provide some level of protection-you can click through to them in the article. As a public health researcher, we try to provide recommendations based on the evidence. Typically, we look at multiple studies over time to determine what is effective, but as Ed states: “The coronavirus pandemic has moved so quickly that years of social change and academic debate have been compressed into a matter of months. Academic squabbles are informing national policy. Long-standing guidelines are shifting. Within days, an experiment that’s done in a hospital room can affect how people feel about the very air around them, and what they choose to wear on their faces.” So will I be wearing a mask if I go out? Yes! Especially because we have someone at home who is at higher risk for COVID-19 complications. HOWEVER, I will still be focused on staying at home, washing my hands, not touching my face, and keeping up with social distancing. I am NOT at all an expert in face mask use or infectious disease. However, I have been fascinated by the discussion I have seen about mask use by officials, the media, and in my own social networks. And I have been following the changing guidelines. I am working on some research related to communication about face mask use that has been very interesting! Stay tuned….  Image capture from the CDC on 4/3/20. In today's blog, I wanted to help people understand the idea of emergency preparedness: what it is, how it relates to pandemics, and what people do who work in the field. To explore this, I asked my colleague Samantha Penta to answer a few questions.  Can you tell me a bit about yourself and what you study? I’m an assistant professor of emergency preparedness in the College of Emergency Preparedness, Homeland Security and Cybersecurity at the University at Albany. I view myself as a disaster researcher. My training is in sociology, so I focus on the human and organizational dimension of disasters and other kinds of extreme events. Much of my research has focused on how people and organizations make decisions related to disaster relief, whether that is individuals deciding if and what to donate to disaster relief efforts, or looking at how people plan and implement international medical relief efforts. I’ve studied people’s responses to tornadoes, hurricanes, earthquakes, and the Ebola epidemic from 2014-2016, often looking at how people respond and health and medical issues in disasters. People may hear the word 'preparedness' in the media. Can you describe what that means? The term preparedness can be used in a couple different contexts. It can be used to reflect a state of being (i.e. stating that someone or something is prepared). Preparedness is the name for one of the phases of the emergency management cycle, and it can be used to describe the activities and measures people or organizations engage in. In general, when people talk about preparedness in the context of emergency management, they are referring to things people and groups do to better enable them to respond when a disaster takes place. A common example of these kinds of activities is making a disaster plan or stockpiling a three day supply of food and water. Planning allows people to anticipate what will happen in a disaster and front load that decision-making so they can react faster (and potentially more appropriately). Having a supply of food and water means that if something happens making it difficult to acquire supplies after a disaster, people have the flexibility to ride out that disruption. Are preparedness strategies the same for all possible emergencies? Or are there specific preparedness recommendations just for pandemics? Some preparedness strategies adhere to an all-hazards approach, generally meaning that they are applicable across a range of disasters (think relevant across earthquakes, floods, etc.). Others are more specific to some types of events. Still others lie somewhere in the middle. Take planning as an example. Having a plan and the act of planning for a disaster is relevant whether you are preparing for a hurricane or an epidemic, but there are some things specific to hurricane or epidemics that you would plan for. For instance, households may figure out how they will handle childcare if kids have to say home school for both events, but planning for a hurricane would also involve thinking about where a household might evacuate to and how they get there, while a pandemic plan would be focused on how to stay at home. There are some protective actions that are more specific to particular hazards. I have seen pandemic preparedness guides. For instance, King County in Washington has one. Do you think these guides are being used? There are a lot of factors that can shape if and what preparedness activities people engage in. Sometimes this has to do with people’s risk perception—people who don’t anticipate being affected by an event would be less likely to engage in preparedness activity for it. However, even when people want to engage in preparedness, they may face other obstacles in doing so. Some people may want to stockpile three days of food (or for the COVID-19 epidemic, more like 14 days), but do not have the financial resources to do so. What type of people specialize in preparedness work? And some people may wonder what they do when there are no emergencies going on. What are their jobs typically like? Jobs related to emergency management are everywhere. The type of jobs people immediately think of are folks in local, state, or federal government specifically with an emergency management title, often working in an emergency management agency, like FEMA (the Federal Emergency Management Agency). Emergency management is in other areas of government as well. For instance, within Health and Human Services, there is the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response. However, there are emergency management jobs in the non-profit and private sectors too. There are nongovernmental organizations, such as the American Red Cross or Team Rubicon, for which disaster response is their primary mission or one of their missions. In the private sector, large companies will have individuals or entire teams dedicated to continuity of operations. Basically, their jobs are figuring out how to minimize the disruption to keep the company going in a time of crisis. When people in these fields aren’t actively responding to a disaster, they are still doing important emergency management work. They may be engaging in preparedness activities like planning. They are often trying to find ways to reduce the likelihood of these events from happening or reducing the severity of the disruption caused when these events do occur (this is called mitigation in the emergency management world). In many cases, they are also still supporting people, organizations, and communities recover from the previous event. Long term needs persist long after the event itself is over, and people in this field will work to help these folks bounce back for years after a disaster. There is always work to be done in this field, even when skies are blue. Is there anything else you want to add about emergency preparedness for pandemics? With pandemics especially, it is important for people to adopt a community mindset. Actions people take will directly affect the overall duration and severity of the pandemic, and can shape how individuals experience these events. If people are considering gathering with other people rather than staying home, they need to think not just about the risk to themselves, but the risks they are potentially exposing others to. As people purchase supplies for their personal stockpile, it’s important that they make sure they meet their own needs, the extent to which people may purchases beyond their needs directly affects the availability of resources for others. Communities make it through pandemics in large part due to the actions of people within those communities. Everyone has a part to play in making our communities safer. Keep in mind a pandemic is just one type of emergency situation. It is good for everyone to have a preparedness plan and emergency supplies for any type of event that might occur. Learn more at Ready.gov about how you can prepare, including what supplies you should have.

If you would like to learn more about emergency preparedness in general, you can go to the following websites: Centers for Disease Control Department of Homeland Security FEMA By now most of you have heard the phrase “flatten the curve”. But did you know this idea comes from the field of epidemiology, one of the major fields of study in public health?

Epidemiology, called epi for short, is the “the study (scientific, systematic, and data-driven) of the distribution (frequency, pattern) and determinants (causes, risk factors) of health-related states and events (not just diseases) in specified populations (neighborhood, school, city, state, country, global)”. According to the Centers for Disease Control, “the word epidemiology comes from the Greek words epi, meaning on or upon, demos, meaning people, and logos, meaning the study of. In other words, the word epidemiology has its roots in the study of what befalls a population.” Epidemiology experts, known as epidemiologists, study the frequency of events that impact the health of populations and look for patterns that may be happening. They also seek causes of disease or other health concerns. They do not just study infectious disease and disease outbreaks. They also look at injury and violence trends, environmental health issues, birth defects, and cancer, among other topics. Many epidemiologists have either a Masters of Public Health Degree, or a PhD in epidemiology. Some have other degrees as well. Have you ever heard of John Snow? He conducted one of the first epidemiology type studies in London where there was a big cholera outbreak. He figured out it was being caused by a water pump on Broad Street that was a main source of water. I found this easy to understand 5 minute video if you want to learn more about him and what he did. His work eventually led to major changes in water systems. Some epidemiologists work at universities as professors. These epidemiologists do research, teach classes, and train future epidemiologists who will go on to work in the field. Others work in research centers or institutes. There are many epidemiologists on twitter who are sharing some great information…if you are on twitter check out the hashtag #AnActualEpidemiologist to find some to follow. Other epidemiologists work at all levels of government. This letter from an epidemiologist who works at a local health department in Virginia gives you a sense of what they do at the local level. Epidemiologists also work at a range of other places such as insurance companies and hospitals. If you want to learn more about epidemiology and how outbreaks are studied, this free course is now being offered by Johns Hopkins at Coursera: https://www.coursera.org/learn/covid19-epidemiology You can learn more about “epi curves” at this CDC link in just ten minutes: https://www.cdc.gov/training/QuickLearns/epimode/ The CDC also has resources for classrooms if you are looking for activities to use with your children or students: https://www.cdc.gov/careerpaths/k12teacherroadmap/classroom/index.htm Almost everyone is dealing with a range of challenges during this current pandemic. There are many people who are more vulnerable, have extra concerns, or are managing difficult situations for a variety of reasons. Those of us who have children with disabilities face some unique issues. I recently co-wrote an article about this topic with a friend of mine and collaborator who is a pediatrician. We both have a child with disabilities and thought it was important to present this perspective. The article was published by Scary Mommy this weekend. You can read it by clicking here.

We are all hearing the term public health a lot lately. What does it mean?

The American Public Health Association is the main professional organization for people working in public health. They state that “Public health promotes and protects the health of people and the communities where they live, learn, work and play.” Health care providers such as doctors, nurses, physical therapists and dentists treat individuals. The focus is on diagnosing a medical problem and providing a treatment for it. People working in public health focus on many people. We think about how we can improve the health of an entire community or group. We look at causes of health problems and how we can change laws, the environment, communities, or organizations to improve the health of many. For example, people working in public health might help identify a cancer cluster in a location and then try to determine what the cause is. For now, if you want to learn more about public health in general, take a look at this 5 minute video. Note the car crash example. If someone gets hurt in a crash, a doctor is the one who treats the injuries. People working in public health think about issues like whether the person is able to get the care they need, driving laws, road safety, and if the person has enough social support to help with their recovery. In future blog posts, I will introduce you to different areas of public health and discuss how each one plays a role in addressing COVID-19. Some examples are health policy, epidemiology, community health, and my favorite, health communication.  Dear students, Tuesday I had to stop by my office and was greeted by an empty hallway. It was eerily quiet. And then it hit me. I may not see any of you in-person for a while, and I may not get to celebrate graduation with you this year. Some of you may be feeling anxious about how you will complete your classes, independent studies, or internships. Know that I am available to help you navigate through these challenges. Some of you may be feeling sad that you have to leave campus especially if you are a senior. This is not how you expected the end of your senior year to go after all of your hard work. I understand! If you are having trouble focusing on getting work done, know that you are not alone. I am too! We are all juggling many things right now, dealing with different challenges, and managing a lot of unknowns. Remember that we are part of a community and people are here to help. I know many of my current and former students are working in the field. If you are with the federal government, or state or county health departments, know that you are making significant contributions to the public health response. If you are a health care provider, know that everyone appreciates what you are doing right now. Many of you are putting yourselves at risk to help others who are sick and for that we are incredibly grateful. Some of you may be doing work that is important in other ways. Thank you! And if you are wondering what you can do to help, there is always a need for people to promote clear and accurate information among their social networks. Help people understand what they need to do and why. As a current or former public health student, you are lucky to have a unique insight into what is going on. Whether it is health communication, epidemiology, health policy, or other public health fields, all aspects of public health are playing a role in addressing the current pandemic caused by COVID-19. Please take care of yourself and know you are in my thoughts. Practice social distancing if you can while staying engaged with your social networks, take social media and news breaks, and reach out if you need help finding resources. Stay safe, Professor Manganello Welcome!

As someone who studies and teaches about health communication, I have always been interested in finding ways to give people clear and useful information about public health. I have seen a lot of people become interested in public health during the COVID-19 pandemic. And since I am mostly home these days, I thought it was a good time to try out a blog! For this first blog post, I want to let people know what the blog is about. What is GetHealth'e' and why is the blog on this site? Get Health'e' means to "get health literate using 'e'lectronic tools". I have been working for a while on creating ways to help people improve their health literacy. I created the GetHealth'e' website as a way to teach people about health literacy and provide links to good resources. I also started a YouTube channel that is a work in progress. And I have been seeking funding to create online classes that people can take. Please let me know if you have ideas about other things you would like to see on the site! What can you expect to see in this blog? I will be spending a lot of time at least for now talking about COVID-19. Learning about public health in general is also important to understand the pandemic and the response to it so expect to see posts about public health. I will link to news stories about health and discuss what they mean, and also plan to have my public health friends write guest blog posts. And you will probably see posts about my classes, media, my family, my big fluffy cat, and fun memes and videos. Thanks for reading! Please let me know if you have questions you want me to try to answer or if there are topics you want to know more about. I look forward to giving this a try...wish me luck! Jen Manganello |

AuthorJennifer Manganello is a public health professor and mom of two boys living in upstate New York. Archives |

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed